News

Hybrids vs diesels vs electric cars: Total cost of ownership compared

Without government concession programs, BEV does not seem to be a financially viable alternative, even when fossil fuel prices are high.

BHPian pqr recently shared this with other enthusiasts.

HEV vs. Diesel vs. BEV: Total cost of ownership study:

The mid-size SUV segment in India now has three low-running-cost vehicle options available, based on different technologies: conventional diesel engine (ICE) from Hyundai-KIA; strong hybrid (HEV) from Toyota-Maruti; and pure electric (BEV) from MG. There are numerous use cases, and each product and technology comes with its own set of advantages and limitations. So which one to choose?

Toyota has been claiming that HEV technology is the right transitionary path to BEV adoption, and to walk the talk, Toyota brought strong hybrid technology to the masses in India in the form of the Toyota Hyryder, based on its non-identical twin, the Maruti Grand Vitara. MG has also launched the ZS EV facelift this year with an updated battery pack. The Hyundai Creta is due for a facelift early next year.

Safety:

The European MG ZS EV received a five-star rating in the 2019 Euro NCAP crash test. ZS EV are imported as CKD units and are assembled at MG India’s plant in Halol, Gujarat. The Hyundai Creta only received a three-star rating in the GNACP frontal offset crash test (old protocol). The Toyota Hyryder is yet to be tested.

Dimensions:

Exterior dimensions can be deceptive, because actual usable in-cabin and boot space depends on overall packaging done by designers and engineers, and potential buyers need to examine cars in person and make a final decision based on family needs.

Power & torque:

The MG ZS EV has a very powerful drivetrain and offers exhilarating performance, typical of most BEVs. Perceived value for exhilarating performance needs to be mentally factored in at the time of relative price to value analysis. Hyryder’s hybrid system is only tuned for efficiency, and the fun factor took an extreme back seat. The power to weight ratio gap is 17 PS per ton. Though the power output of the Hyundai Creta is the same as the Toyota Hyryder, the high torque output of the diesel engine makes the real difference, along with the smooth torque convertor transmission. For drivability, potential buyers need to take a test drive themselves or may refer to several available reviews.

Features:

Feature-wise, all products are well matched, covering all the basics with some differentiators.

Total ownership cost = purchase cost + running cost + maintenance cost differential.

Now this study will focus on the theoretical customer benefit part, i.e., the total ownership cost that includes purchase cost, running cost, and maintenance cost differential. Since use cases vary a lot, this study will be more of a theoretical exercise, and the outcome is more indicative than a definitive conclusion.

Starting point:

Higher fuel efficiency leads to lower average running costs, which offset the higher initial cost of purchase of vehicles, thus delivering a higher monetary benefit over the long term, provided the vehicle covers higher mileage every year.

Assumptions and caveats:

Efficiency:

- Overall efficiency claimed by manufacturers is considered here for running cost calculation.

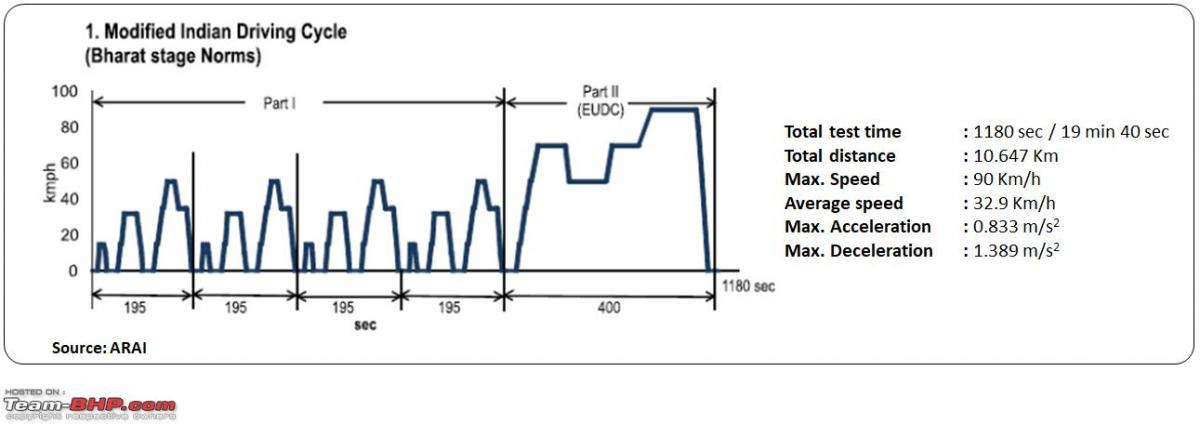

- Manufacturer claims are based on the Modified Indian Driving Cycle (MIDC) and were tested on a dynamometer in a controlled laboratory environment.

- Vehicles are tested at an average speed of 32.9 km/h with a maximum speed reaching up to 90 km/h. All auxiliary power consumption units are switched off (AC compressor, headlamps, infotainment system, etc.).

- Real world efficiency would be different due to different load conditions, speed, gradient, idling, and auxiliary load (AC compressor).

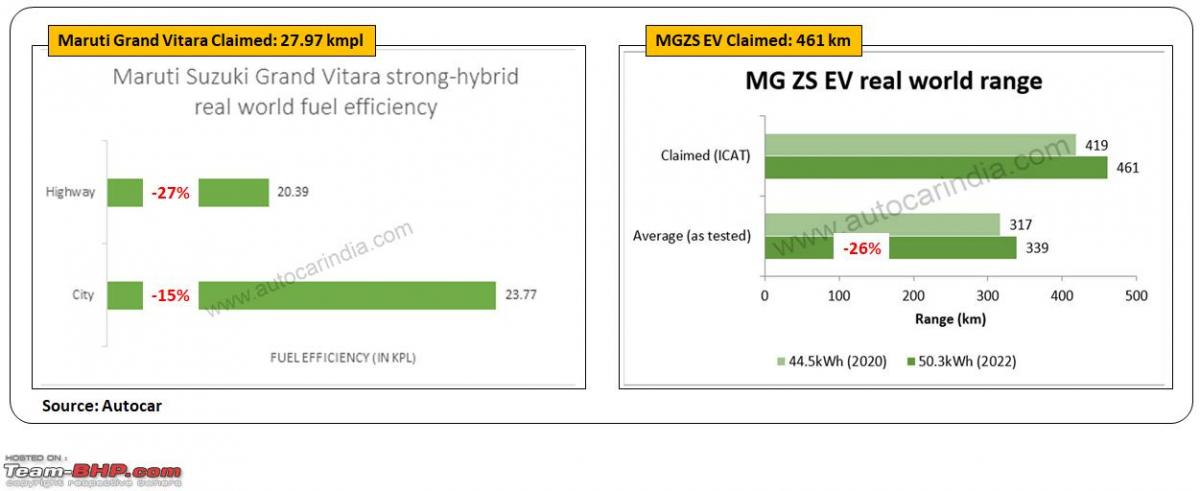

- This can be seen in the Autocar real world fuel efficiency test as well. Real world efficiency varies from claimed figures by 15% to 27% in the case of the Maruti Grand Vitara HEV and 26% in the case of the MG ZS BEV.

- For indicative comparison, MIDC values hold good, since all vehicles are tested under the same conditions with pre-conditioning.

- Due to regenerative braking, HEVs and BEVs are typically more efficient in stop-go city driving conditions.

- However, efficiency will come down during highway driving as the engine will stay on for most of the time in the case of HEV and regenerative braking could be limited in the case of both HEV and BEV.

- On the other hand, diesel engines will be more efficient during highway runs than in city conditions.

Battery life and resale value:

- What is the biggest unknown here is the resale value of products with HEV or BEV technology in India.

- Moreover, manufacturers never tell the actual battery life and cost of replacement at the time of product launch or sale, though they know the facts due to endurance tests they undertake during the product development phase.

- This is the area where potential buyers and existing customers will largely remain in the dark before reality hits them (if ever) in the form of battery replacement costs and affect on the resale value.

- Because of technological advancements, the current generation of BEV product range may become obsolete in the future.

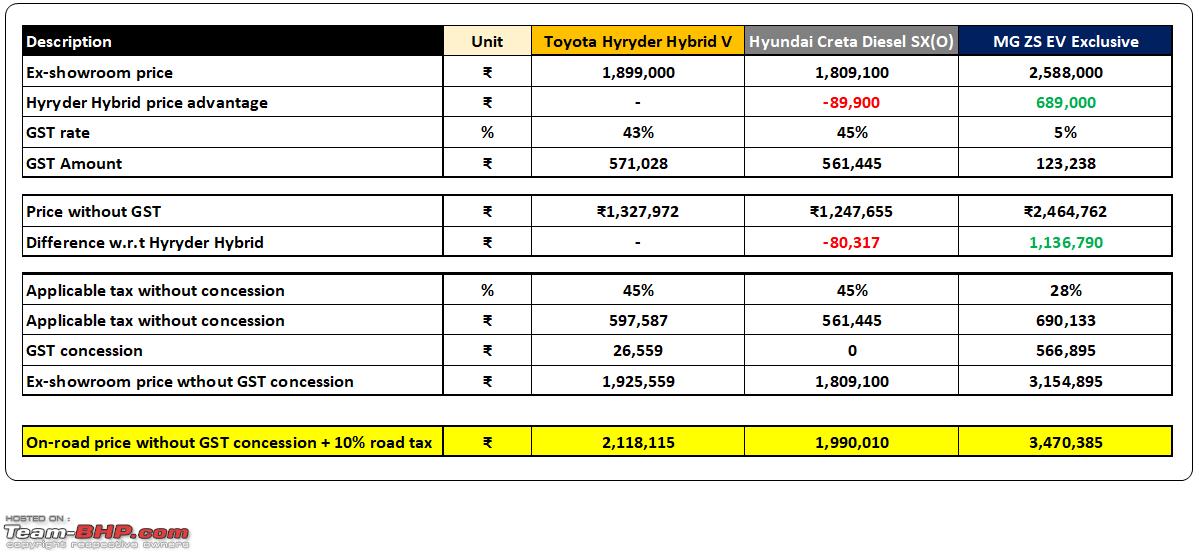

On-road price:

- There are many states where BEVs are exempt from the 15-year road tax, and that has been factored into the BEV on-the-road price.

- Road taxes vary from state to state. Here, the average rate is considered to be 10% for ICE and HEV.

- Because the minimum insurance cost as a percentage of the car price and TCS remain largely unchanged, they have not been considered here.

- The regular maintenance cost of diesel and petrol ICE is factored in, as other costs (tyres, brake pads, etc.) remain the same for BEV.

- The MG ZS EV is imported through the CKD route and is subject to customs duty, resulting in a pricing disadvantage.

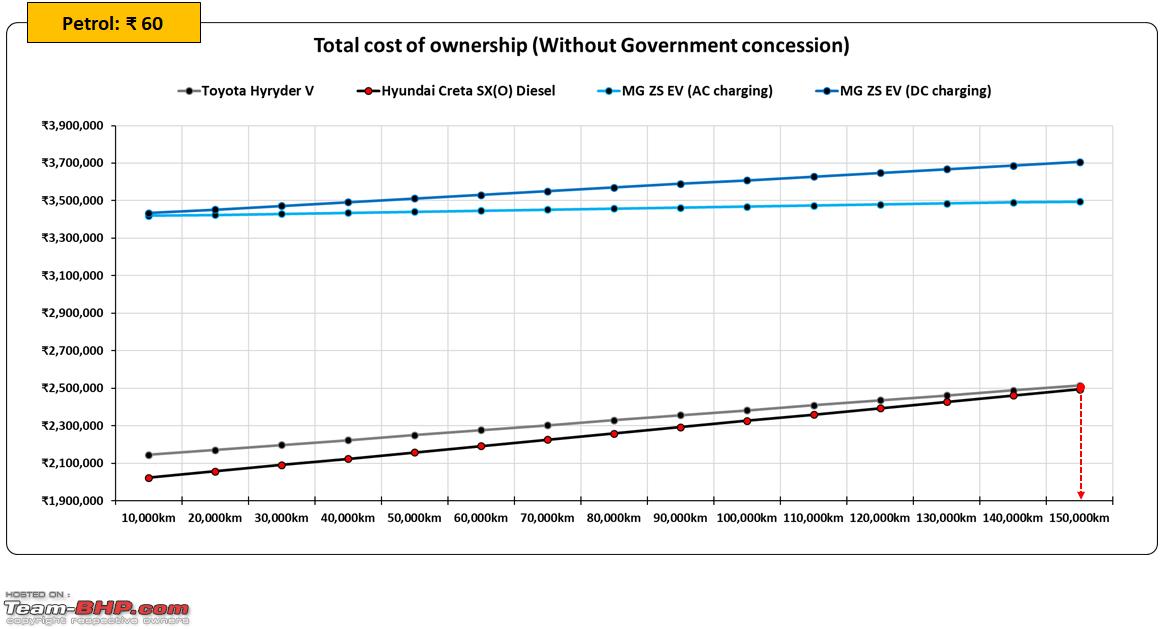

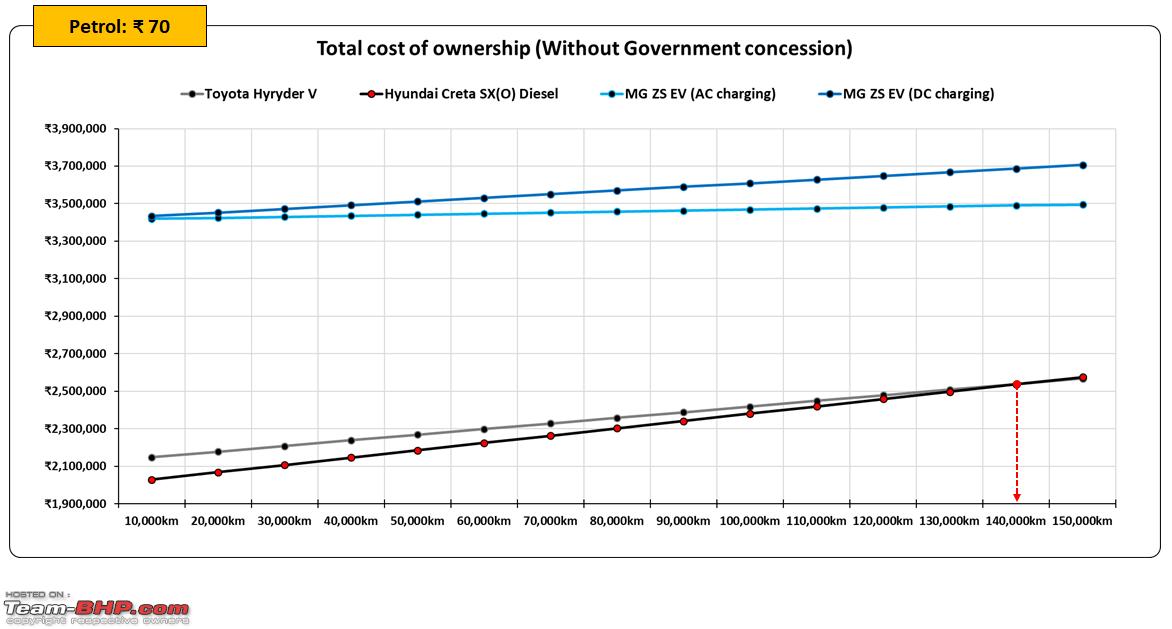

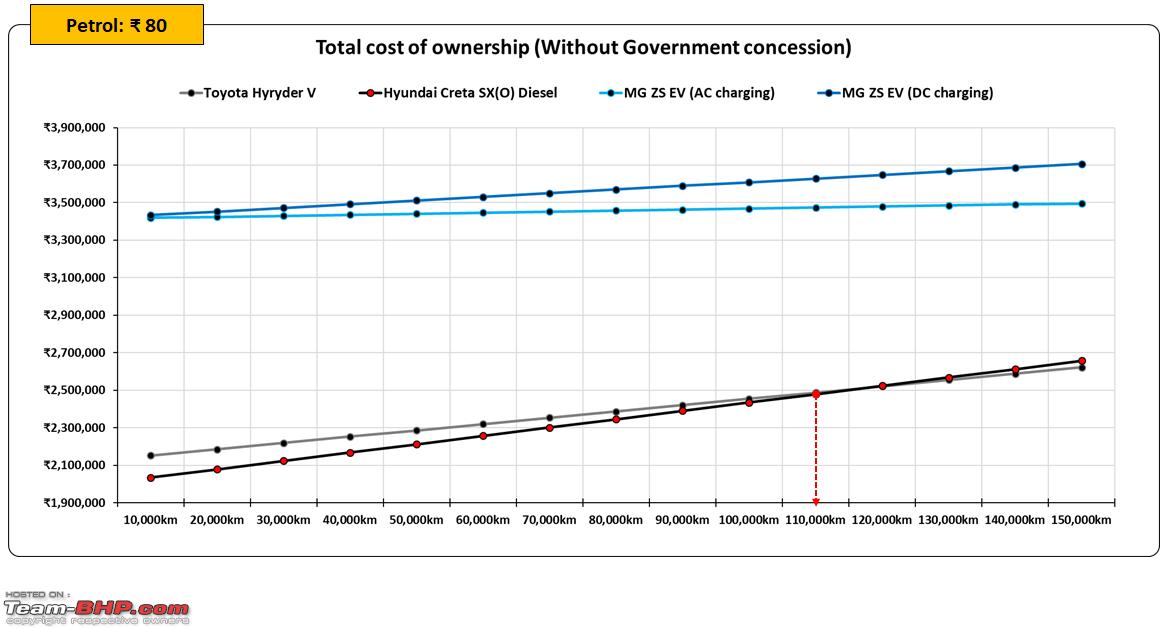

Break even simulation: Based on changing fuel price:

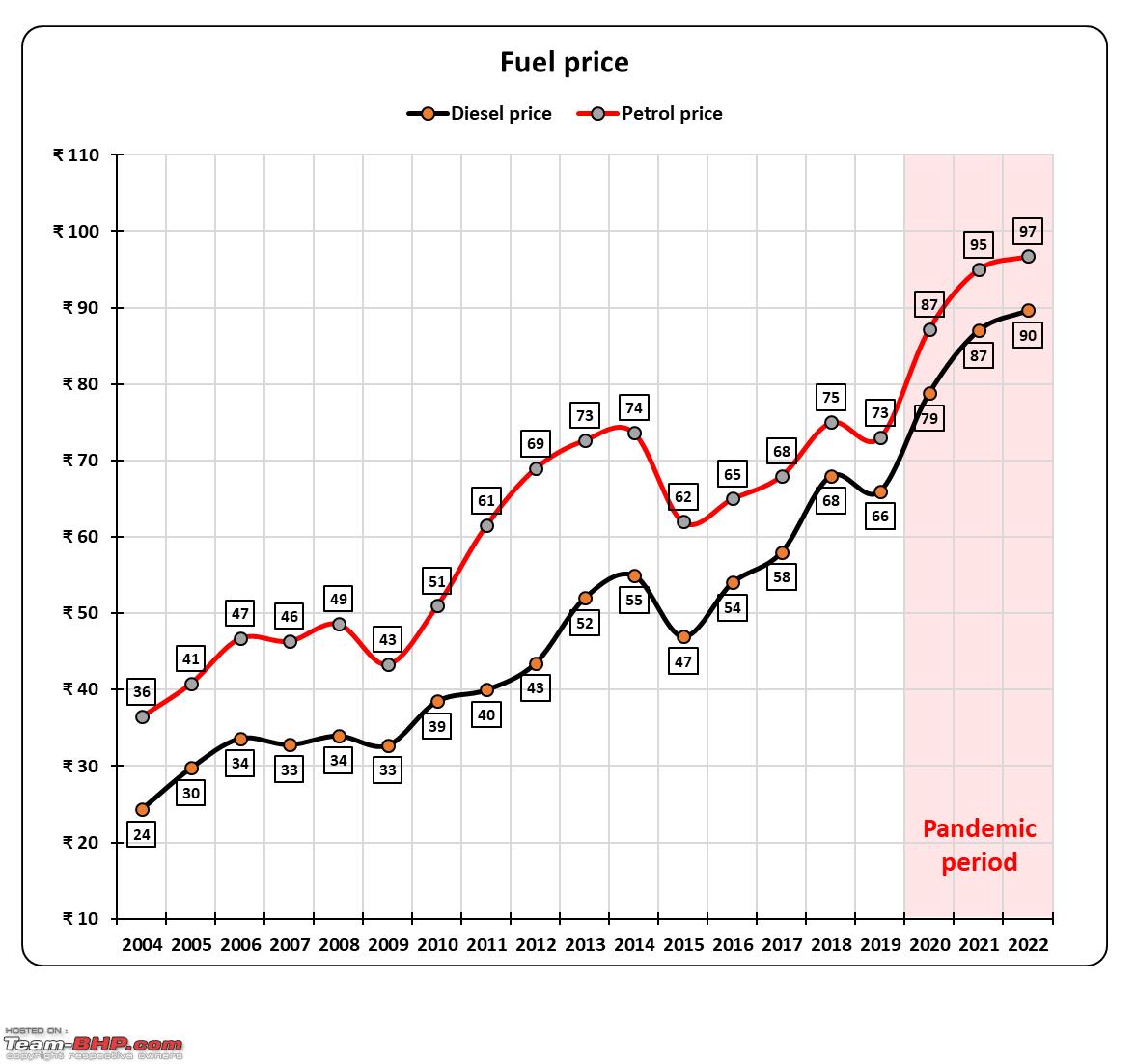

Fuel prices vary a lot over a time period as they are subjected to a lot of factors. From 2017 onwards, petrol and diesel price differences came down, thus reducing the running cost benefit diesel engines have.

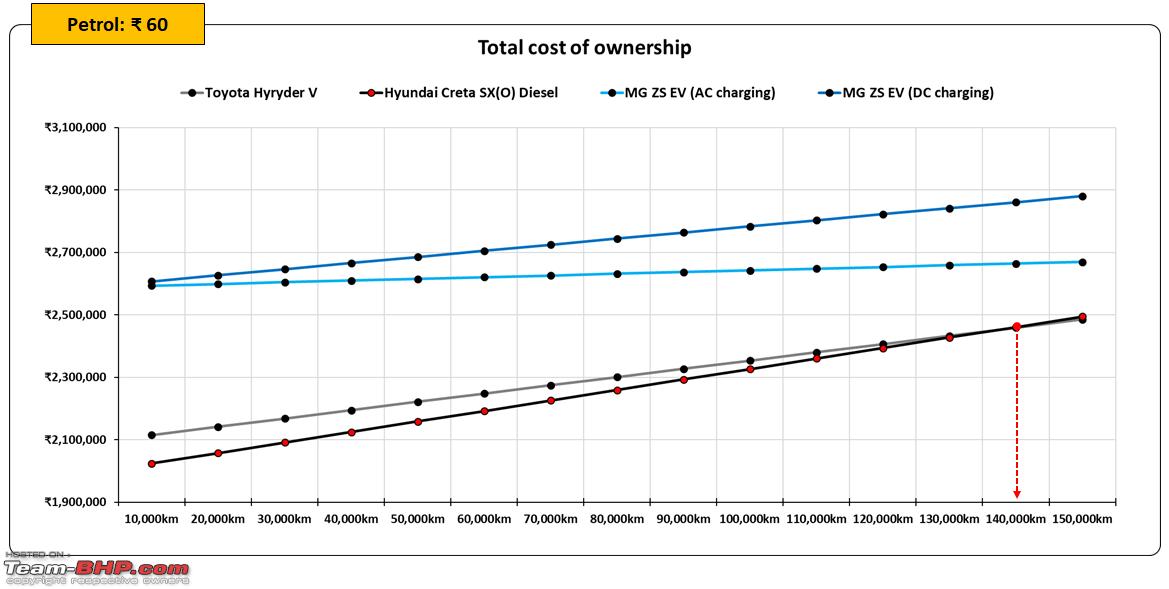

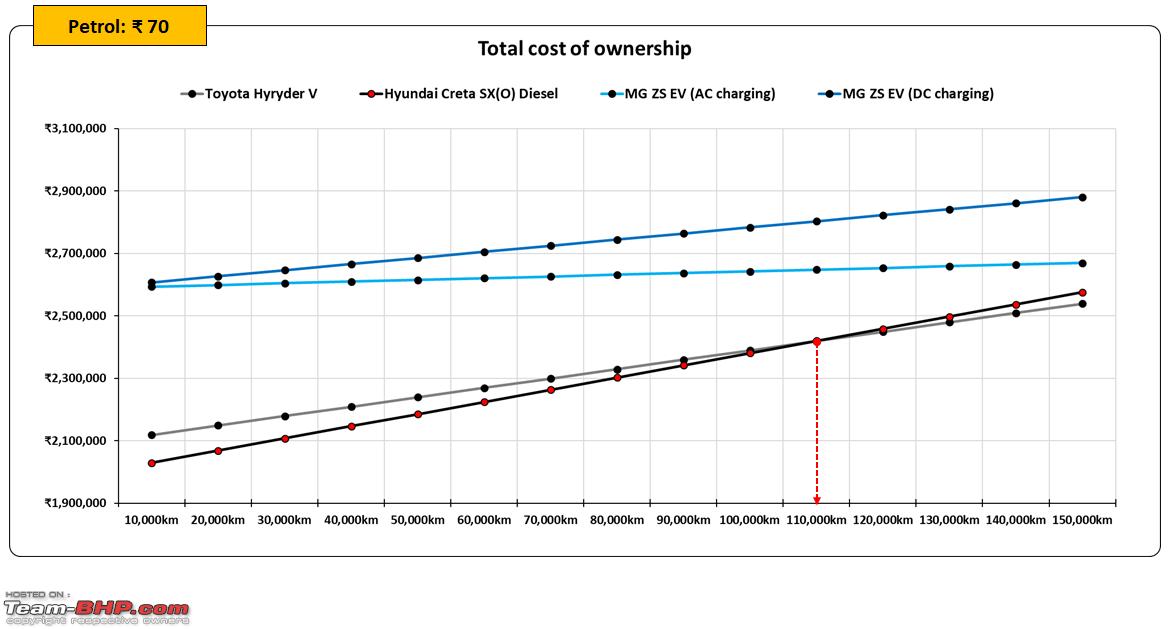

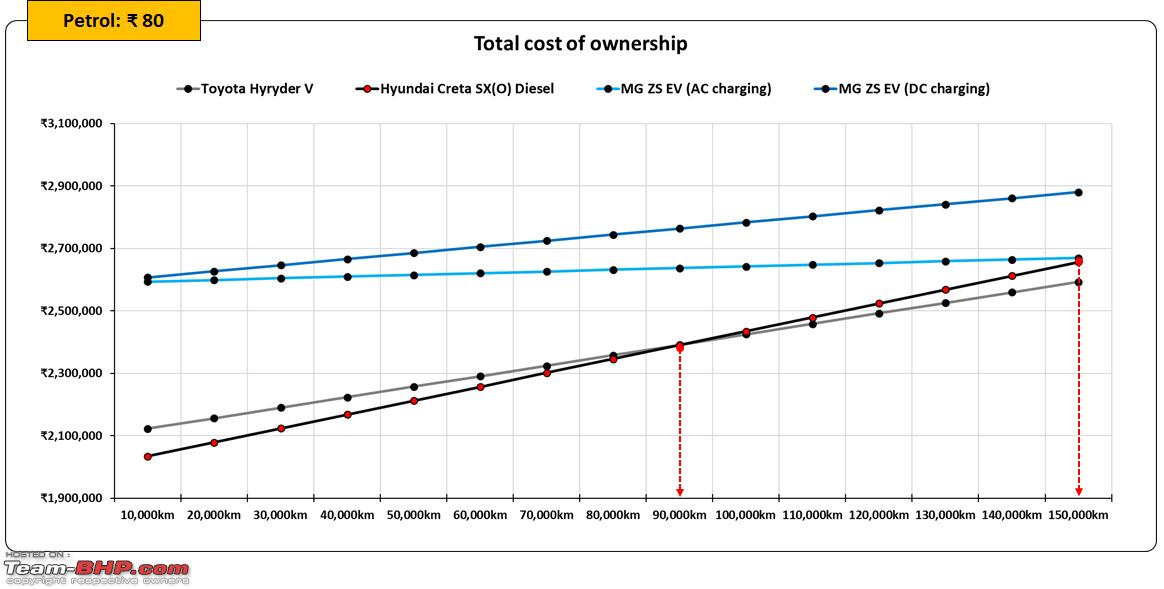

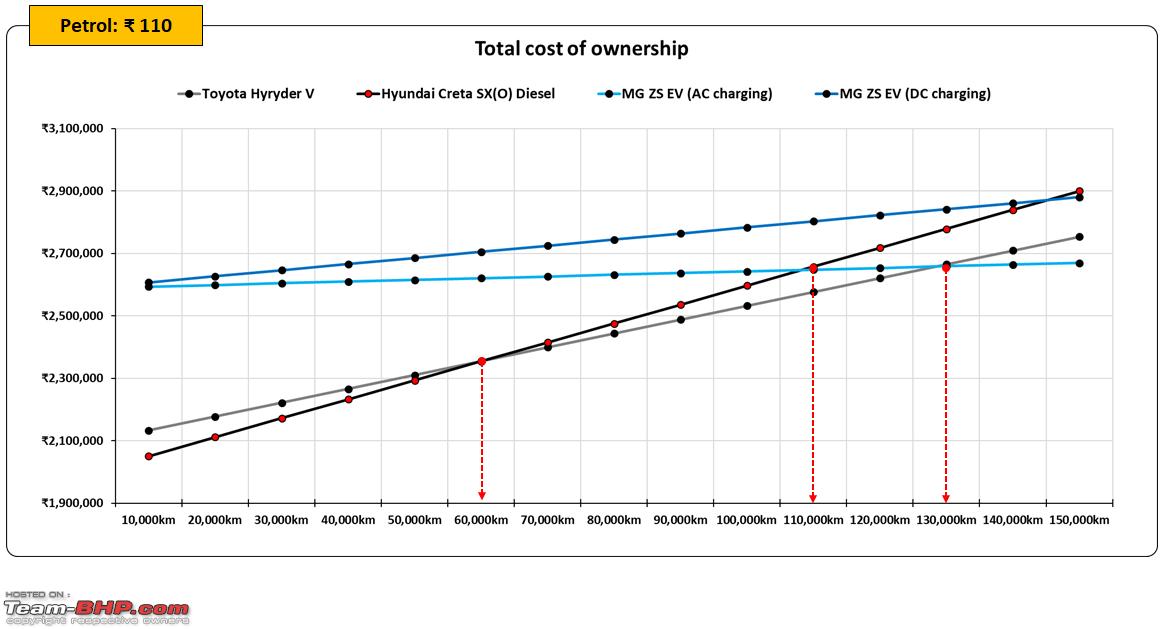

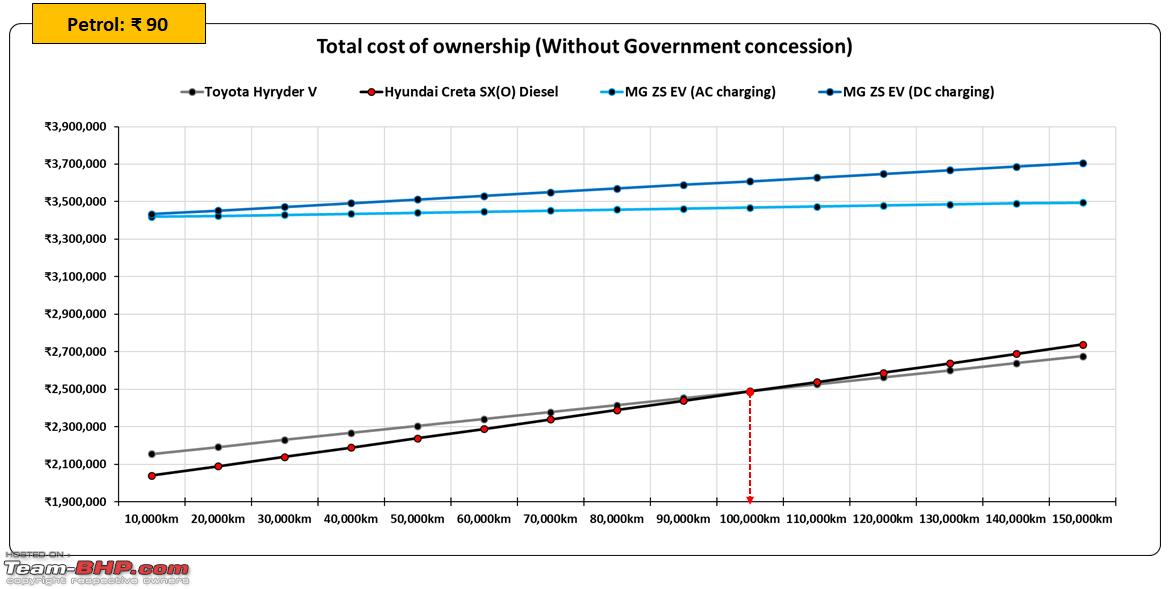

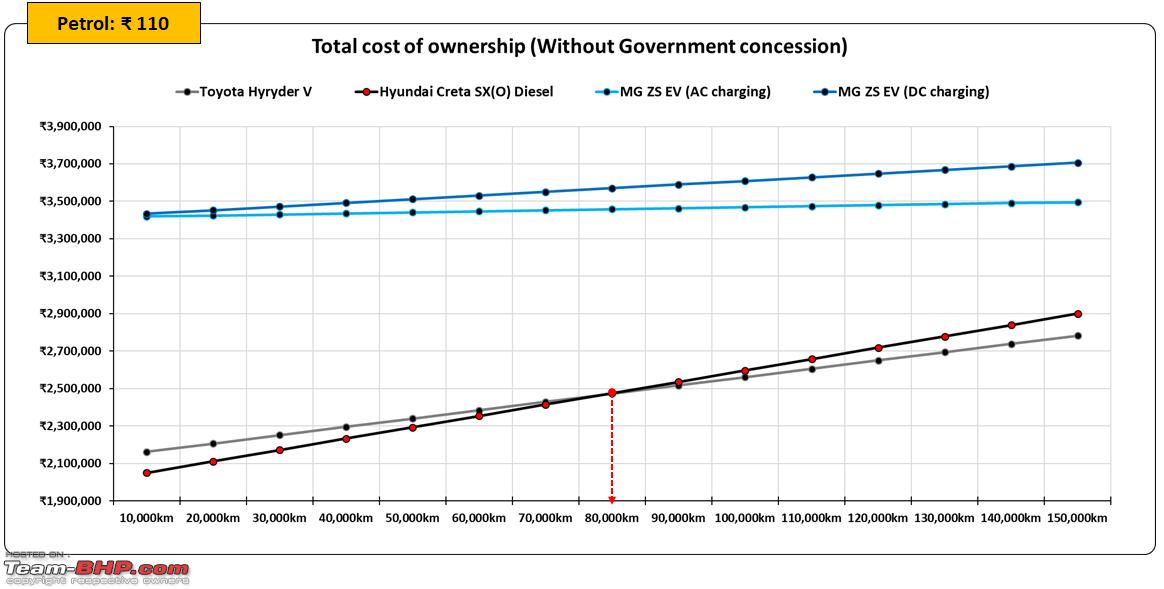

Below is the break-even simulation based on different fuel prices:

Break even analysis:

In the pre-pandemic era, average fuel prices remained below ₹ 80. However, in the last three years, fuel prices have gone through the roof, and the cost of running has become an even more crucial factor in purchase decisions.

The below table summarizes the indicative breakeven point based on different petrol price points. A purchase decision has to be based on an individual's use case and charging convenience:

- Higher running within the city and higher fuel prices make the case for HEV and BEV against diesel.

- Diesel makes more sense when fuel prices are low or highway usage is high.

- Special case of NCR: National Green Tribunal (NGT) in April 2015 banned diesel vehicles more than 10 years old and petrol vehicles more than 15 years old from plying within Delhi-NCR. Due to NGT rules, HEV will have a 5 year advantage over diesel in the NCR region, and BEV has no disadvantage at all.

- Unknown rechargeable battery life in Indian driving conditions (temperature, moisture, etc.) is the biggest blind spot as of now. Unknown to customers but well known to manufacturers, what a shame!

Scenario 2:

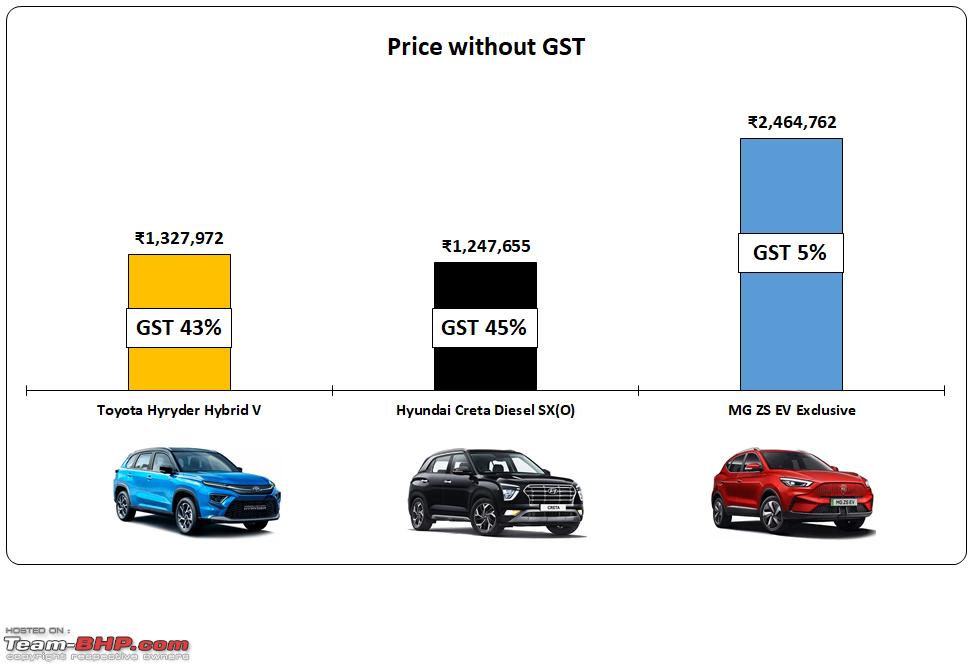

BEVs in India are taxed at a 5% GST rate, whereas strong hybrids longer than 4m in length have a 43% GST incidence. The 15-year road tax is also exempt in many states for BEVs. These two government concessions make BEV a viable option for reducing pollution in the immediate vicinity. But are BEVs really a financially viable alternative to HEVs and pure ICE in the long term without government support? Let’s try to examine that aspect too.

Without applicable tax, the BEV is ₹ 11,36,790 more expensive than the HEV. What should be kept in the back of the mind is that the MG ZS EV comes through the CKD import route and is more powerful.

The simulation below is based on the non-concessional price of HEV and BEV:

Analysis:

Without government concession programs, BEV does not seem to be a financially viable alternative, even when fossil fuel prices are high. To what extent local production of cars and cells built under the ACC PLI scheme with imported raw materials in India, along with economies of scale in battery production, bridge such a wide gap in cost in coming years? Only time will tell.

Green credential:

If grid electricity's CO2 footprint is factored in, the BEV loses its green credential. But then that’s not BEV’s fault; this is due to the heavy reliance on fossil fuels as a major power generation source in India. Pure solar-based charging points are far and few, and mostly not viable in heavily urbanized regions of India.

For the time being, BEVs are only assisting in shifting pollutants to the location of thermal power generation due to zero tailpipe emissions. What India needs is an urgent and rapid diversification of renewable power generation sources.

Check out BHPian comments for more insights and information.